COVID-19: learning from experience

- The Lancet

Published:March 28, 2020 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30686-3

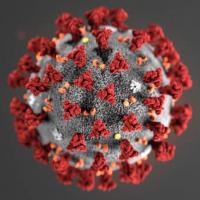

Over the past 2 weeks, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has marched relentlessly westward. On March 13, WHO said that Europe was now the centre of the pandemic. A few days later, deaths in Italy surpassed those in China. Iran and Spain had also reported over 1000 deaths as of March 23, and many other European countries and the USA reported increasing numbers of cases, heralding an imminent wave of fatalities.

Following the sweep of COVID-19 is a series of dramatic containment measures that reflect the scale of the threat posed by the pandemic. Lockdowns that seemed draconian when instigated in Wuhan only 2 months ago are now becoming commonplace. However, many countries are still not following WHO’s clear recommendations on containment (widespread testing, quarantine of cases, contact tracing, and social distancing) and have instead implemented haphazard measures, with some attempting only to suppress deaths by shielding the elderly and those with certain health conditions.

The initial slow response in countries such as the UK, the USA, and Sweden now looks increasingly poorly judged. As leaders scramble to acquire diagnostic tests, personal protective equipment, and ventilators for overwhelmed hospitals, there is a growing sense of anger. The patchwork of harmful initial reactions from many leaders, from denial and misplaced optimism, to passive acceptance of large-scale deaths, was justified by words such as unprecedented. But this belies the damage wrought by SARS, Middle East respiratory syndrome, Ebola virus, Zika virus, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and a widespread acceptance among scientists that a pandemic would one day occur. Hong Kong and South Korea were tested by these previous emerging infections, leaving them better able to scale up testing and contact tracing.

Globally, many people are afraid, angry, uncertain, and without confidence in their national leadership. But alongside these dark sentiments, images of solidarity have emerged. Health workers have shown an incredible commitment to their communities and responded with compassion and resolve to tackle the virus despite challenging and sometimes dangerous conditions.

Neighbours have organised to support vulnerable people; businesses and national governments have stepped up to provide support for those who need it and strengthen social security and health services. The pandemic has also brought examples of international solidarity, with the sharing of resources, information, and expertise from countries further ahead in the epidemic, or with better results in controlling the spread.

China’s experience will be crucial to understanding how to lift restrictions safely.Inevitably, the next wave of infections will hit Africa and Latin America. The Africa CDC has reported cases in 41 countries; Brazil, Mexico, and Peru have all reported hundreds or thousands of cases. Most African or Latin American countries have only tens or hundreds of ventilators, and many health facilities do not have even basic therapies such as oxygen. Fragile health-care systems would soon be overwhelmed should infection spread widely.

People living in poor, overcrowded, urban areas are especially vulnerable; many do not have basic sanitation, could not self-isolate, and have no paid sick leave or social security. In response to the threat, WHO has launched the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund, which has raised more than US$70 million, and some regional organisations have taken strong proactive action, sharing information and receiving donations of testing kits and medical supplies.

Many national governments have responded swiftly, but many are yet to take the threat of COVID-19 seriously—eg, ignoring WHO’s recommendation on avoiding mass gatherings. Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro has been strongly criticised by health experts and faces an intensifying public backlash for what is seen as his weak response.Alongside the deep distress felt as many countries experience a peak in cases or brace for it, there is also a growing understanding about the importance of the collective and community.

Europe and the USA have shown that putting off preparation, in either the hope of containment elsewhere or a mood of fatality, is not effective. It is imperative that the global community takes advantage of this spirit of cooperation to avoid repeating this error in more vulnerable countries. WHO has provided consistent, clear, and evidence-based recommendations; communicated effectively; and navigated difficult political situations shrewdly. The world is not lacking effective global leadership. The central role played by WHO in coordinating the global response must continue, and countries and donors need to support WHO in these efforts.

Source: the Lancet