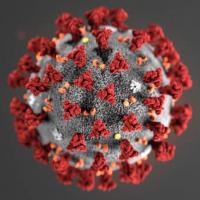

Scientists have identified at least eight strains of coronavirus as the bug wreaks havoc spreading across the globe.

More than 2,000 genetic sequences of the virus have been submitted from labs to the open database NextStain, which shows it mutating on maps in realtime, according to the site.

Think of the open-source project Nextstrain.org as an outbreak museum. Labs around the world contribute genetic sequences of viruses collected from patients, and Nextstrain uses that data to paint the evolution of epidemics through global maps and phylogenetic charts, the family trees for viruses.

So far, Nextstrain has crunched nearly 1,500 genomes from the new coronavirus, and the data already show how this virus is mutating—every 15 days, on average—as the COVID-19 pandemic rages around the world.

As menacing as the word sounds, mutations don’t mean the virus is becoming more harmful. Instead, these subtle shifts in the virus’s genetic code are helping researchers quickly figure out where it’s been, as well as dispel myths about its origins.

Researchers said the data, which includes samples every continent except Antarctica, revealed the virus is mutating on average every 15 days, National Geographic reported.

But Nextstrain cofounder Trevor Bedford said the mutations are so small that there is no strain of the virus that is more harmful.

“These mutations are completely benign and useful as a puzzle piece to uncover how the virus is spreading,” Bedford told the outlet.

He said the various strains allow researchers to see whether community transmission is widespread throughout a region, which can inform whether lockdown measures have been effective.

“We’ll be able to tell how much less transmission we’re seeing and answer the question, ‘Can we take our foot off the gas?’” Bedford said.

Charles Chiu, a professor of medicine and infectious disease at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, said that the database also provides insight into how the virus is moving throughout the US, according to USA Today.

“The outbreaks are trackable,” Chiu said. “We have the ability to do genomic sequencing almost in real-time to see what strains or lineages are circulating.”

Most of the cases on the West Coast are linked to a strain first identified in Washington state, which is only three mutations away from the first known strain, the outlet reported.

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, the virus appeared to have come from China to Europe and then to New York and other states.

But Kristian Andersen, a professor at Scripps Research, cautioned that the maps don’t show the full picture of the spread of the virus.

“Remember, we’re seeing a very small glimpse into the much larger pandemic,” Anderson told USA Today. “We have half a million described cases right now but maybe 1,000 genomes sequenced. So there are a lot of lineages we’re missing.”

Tracking cases through mutations

Bedford’s lab has been using genetics to track the new coronavirus, known as SARS-CoV-2, since the first U.S. cases started to multiply in Washington State in February and March. Back then, public health officials focused on tracking patients’ travel histories and connecting the dots back to potentially infected people they’d met along the way.

Meanwhile, Bedford and his team turned to unlocking the virus’s genetic code by analyzing nasal samples collected from about two dozen patients. Their discovery was illuminating: By tracing how and where the virus had changed over time, Bedford showed that SARS-CoV-2 had been quietly incubating within the community for weeks since the first documented case in Seattle on January 21. The patient was a 35-year-old who had recently visited the outbreak’s original epicenter in Wuhan, China.

In other words, Bedford had scientific proof that people could unknowingly be spreading the coronavirus if they had a mild case and didn’t seek care, or if they had been missed by traditional surveillance because they weren’t tested. That revelation has fueled the frantic lockdowns, closures, and social distancing recommendations around the world in an attempt to slow the spread.

“One thing that’s become clear is that genomics data gives you a much richer story about how the outbreak is unfolding,” Bedford says.

Nextstrain’s visualization tools have also helped engage a public that’s hungry to learn about the science of the coronavirus, says Kristian Andersen, a computational biologist at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, whose lab has contributed more than a thousand genomes, including West Nile and Zika viruses, to the project.